Partner Content

This content was paid for by Jefferson Enterprise and created by INQStudio. The news and editorial staffs of The Inquirer had no role in this article’s creation.

This content was paid for by Jefferson Enterprise and created by INQStudio. The news and editorial staffs of The Inquirer had no role in this article’s creation.

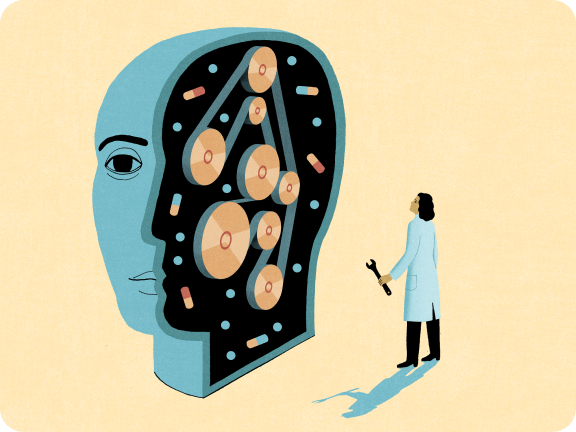

Chapter 1: Brain Science

Peace of Mind

How understanding trauma and the evolution of the brain can help us manage the mind’s misfires.

Imagine you’re driving to work when, suddenly, a car comes speeding up behind you, honking and menacingly flashing its headlights.

Your amygdala, which processes emotional responses to danger, kicks in, initiating a complex cascade of changes in your brain that prepare you to respond.

“Fight or flee?” Your hypothalamus, responsible for this response, is activated. Your heart rate spikes and adrenaline and cortisol flood your system. “Let’s fight,” your brain says. You honk your horn and slam the brakes.

The offending driver swerves around you, pulls over to the shoulder, and hops out of their car. You do the same even though you know better. Your prefrontal cortex, responsible for decision-making and impulse control, is fighting a losing battle with your amygdala’s intense response.

But as you get closer, you see the woman in the back of the car delivering her baby. You notice the other driver is apologizing while trying to help with the delivery. Their sincere look of contrition breaks the spell. “Threat neutralized,” your brain says. Your prefrontal cortex, which had gone offline, regains control as you apologize for your own reaction and ask how you can help.

The structures in our brain’s limbic system control our emotional and behavioral responses. These were among the first parts of the human brain to evolve.

Perceiving a threat on the road, the emotional amygdala kicks your body and brain into high gear.

The hippocampus, the memory box of your brain, is activated by your amygdala. It recalls a traumatic rear-ender you once experienced, heightening your anxiety.

The hypothalamus spikes your heart rate and adrenaline. Your sympathetic system has been activated. We are now in “fight or flight” mode.

Your logical prefrontal cortex combats your amygdala’s impulsivity. It wins, calm prevails. It loses, chaos reigns.

The orbitofrontal cortex helps moderate aggressive reactions by integrating information from different parts of the brain. That’s why the sight of a friendly facial expression calms you down.

“Our brains are biologically programmed to survive,” says Dr. Jeanne Felter, chair of the Counseling & Behavioral Health department at Thomas Jefferson University. “There are certain kinds of universal reactions and responses that we all have to a perceived threat.”

Driving is just one of many modern situations that can set off this type of aggressive response in all of us. To your brain, in that moment, the other car might as well have been a charging bison. These modern scenarios threaten to trigger evolutionary “misfires” in our reactions — disproportionate responses that can explode into instances of aggression and violence.

In his book, Why We Snap, National Institutes of Health neuroscientist R. Douglas Fields unpacks nine triggers of rage that were relevant and useful for most of our existence as a species, but that now can spark dangerous or aggressive behavior. Our tendency to respond to provocation with violence, defend our clan with life and limb, and use aggression to obtain or protect resources were once in proportion with the high-stakes life-or-death circumstances our human ancestors faced. Our brains are still evolutionarily wired to defend ourselves, and new science shows that early-life trauma reinforces our instincts toward fight or flight.

Dr. Jeanne Felter, Department Chair,

Counseling & Behavioral Health Department,

Thomas Jefferson University

When we perceive threats, “the lower part of the brain is triggered and we end up in that ‘fight, flee, freeze’ response,” Dr. Felter explains, referring to the temporal lobe region where the amygdala and hypothalamus reside. The temporal lobe had a significant head start in development. Akin to a car’s engine, it is responsible for basic survival functions such as breathing and heart rate, in addition to our fight or flight response.

By contrast, our prefrontal cortex, located in our frontal lobe, is our navigation system, responsible for higher cognitive functions including reasoning, planning, and decision-making. When we’re under threat, our survival functions rev up and take off, overpowering our ability to navigate situations with higher-order thinking.

Species-wide shifts like living in heterogeneous societies, the emergence of deep economic and social stratification, and readily available weapons are just a handful of the situational threats, relatively new to our species, that our brains have not evolved to avoid.

“When you layer trauma and stress [on top of our existing biology], especially when that happens in high doses in childhood, that lower part of the brain is strengthened like a muscle,” making it more liable to take over, Dr. Felter says.

of

When you feel your temper rising, taking slow, deep breaths can activate the parasympathetic nervous system, which in turn can help regulate the amygdala and moderate the fight-or-flight response.

Say someone cuts you off while driving. Remind yourself that to them, you’re just another car on the road — not a mortal enemy. This “cognitive reappraisal” helps snap your brain out of buying into a “them vs. me” scenario that activates your brain’s emotional response.

“My amygdala has been hijacked.” Naming what’s happening to you in the moment can help you regain control when your brain threatens to lose it. This act of self-awareness engages the rational part of your brain and helps you regain control of your thoughts and emotions.

But what if these same vulnerabilities could provide a roadmap to innovative ways that we can make healthy and peaceful interactions with each other the norm? “The potential is great” in terms of possibilities to develop healthy experiences for human beings using our understanding of the brain, says Dr. Felter. “The question is: How do we arm as many people as possible with this knowledge?”

From aggressive to expressive

It’s a question Dr. Felter has repeatedly answered by training non-clinical professionals to understand human trauma and use that critical context to provide healing.

Earlier in her career, at the request of one elementary school principal, Dr. Felter developed a three-part trauma training for teachers. She wanted to help them reframe their conceptualization of students as fundamentally aggressive, manipulative, or attention-seeking when they exhibited certain behaviors, and instead help them see these behaviors as students’ expressions of their needs. “[These behaviors] indicate the student is operating out of their lower brain,” — its emotion center — “and the need is safety,” says Dr. Felter.

For some teachers, the training generated profound realizations about their students’ behaviors. In one session, they discussed how all humans’ sensory input bypasses the “thinking brain” — our prefrontal cortex — and instead enters through its emotion center. It’s why overwhelming environmental stimuli can elicit a strong reaction in some.

“In the midst of one of these trainings, a teacher announced a huge ‘a-ha,’” says Dr. Felter. An underperforming student in the teacher’s math class had been withdrawn and antisocial, and the teacher said she had labeled the student as disrespectful and uncooperative. “Every time she approached to help him he would put his hand in her face and tell her loudly to get away,” says Dr. Felter.

The teacher had a revelation: In class she spoke loudly, was high-energy, and wore bright colors. Her classroom itself was messy and busy. With Dr. Felter’s help, she realized this might overwhelm the student and even make him feel unsafe. “I approach him often from behind and he seems startled. He’s the type of kid that probably has a lot of sensory needs that I’ve never thought about,” she recalled the teacher saying.

Dr. Nicole Johnson, Program Director,

Community & Trauma Counseling Program,

Thomas Jefferson University

Brain meets spirit

Dr. Felter’s Thomas Jefferson University colleague, Dr. Nicole Johnson, runs the University’s Community and Trauma Counseling Program. In 2019, she approached Dr. Felter and Jefferson Associate Professor Dr. Steven DiDonato about creating a trauma training program specifically for faith leaders.

“Being a faith leader myself, I’ve always understood [that] when I entered the clinical world, I stood in two worlds that didn’t always agree or talk to each other,” Dr. Johnson says. “And I recognize that many people will walk into the building of a church before they walk into a mental health agency, so why not educate the faith leaders who are also on the frontline?”

Several times a year, her training sessions teach clergy the foundations of trauma and its impact on the brain. Clergy are incorporating this knowledge into their faith-based work with parishioners. “Now when these faith leaders pray, they’re saying, ‘Lord, heal their brain, because their prefrontal cortex is not online,’” says Dr. Johnson. “The information is powerful because it gives people a context for how they think and act.”

Dr. Jeanne Felter, Department Chair,

Counseling & Behavioral Health Department,

Thomas Jefferson University

Changing tracks

It’s not just people serving communities in counseling-adjacent roles who can do their part to shift our society with this knowledge.

In 2020, transit workers in Philadelphia created a grassroots peer mediation program and sought support to further develop it. As essential workers, they were feeling the impacts of even higher work-related stress in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

A local foundation stepped in and bolstered the program, named “Team Valor,” by adding an emphasis on trauma, and particularly the stress of the job and the impact of community traumas in the neighborhoods the transit system serves. “If you do conflict resolution or peer mediation without focusing on the deep impact of trauma on all of the spaces they interact with, then you’re missing the mark,” says Dr. Felter.

Felter and team are making sure the organization as a whole has a foundational understanding of how trauma shows up both for transit workers and for the riders they serve. Key to their work: context. “We know these transit drivers are often engaging with a really traumatized community,” she explains. In addition to direct counseling that bolsters employees’ own mental health, providing neuroscience-backed instruction and interventions to public-facing employees like transit workers can have a broader impact on the communities they serve.

“As a layperson, knowing how to support and encourage healing and promote environments that encourage healing is really critical,” says Dr. Felter. “Arming community members with knowledge of the brain is vital in every domain where there’s human-to-human interaction.”

Sagan and other scientists who have issued similar warnings understand that the development of our brains, which evolved over millennia as our species adapted to survive in our natural world, has simply not had time to catch up to the modern scenarios and contexts we find ourselves in, or the traumas we’ve faced. By understanding the brain, more of us can get involved in cultivating this shared wisdom. Initiatives vesting this knowledge in everyone from teachers to clergy, and even barbers and bartenders, remind us just how creative we can be as we reimagine our society.

Mind over motor

The next time someone tailgates, take a moment to ground yourself: According to Dr. Felter, deep breathing, with an emphasis on a longer exhale, can shift your brain from a reactive state controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, which triggers the “fight, flight, or freeze” response, to a calmer state controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which fosters a calm and reasoned “rest and digest” response.

Illustrations by Greg Clarke and Lyndsey Matoushek/Getty

Home of Sidney Kimmel Medical College